In this fraught time of coronavirus, I’ll start with a fervent prayer for your wellness, my companions in this blog. A friend commented a few days ago that “isolation is exhausting.” Transitioning from the constant consumption of breaking news and other people’s opinions, to frantic busy-ness at home, to quiet reading and puzzle-solving, to endless online shopping—yes, I am exhausted and I think nearly everyone is by now. My best remedy for such ennui is to write, and so I have opened up my WordPress account and will revive a blog that is ready and waiting for the next post. I hope that my stories will make a connection to something in your life and bring you a moment of peace and perhaps a smile.

Today’s post is a story that I wrote for the Touchmark writing club. Each week residents are invited to submit a story told from their life experiences. This week’s prompt is to write about your most precious childhood possession and why it was important to you. I would love to read your memories and responses in the Comments section!

The Bangle Girl

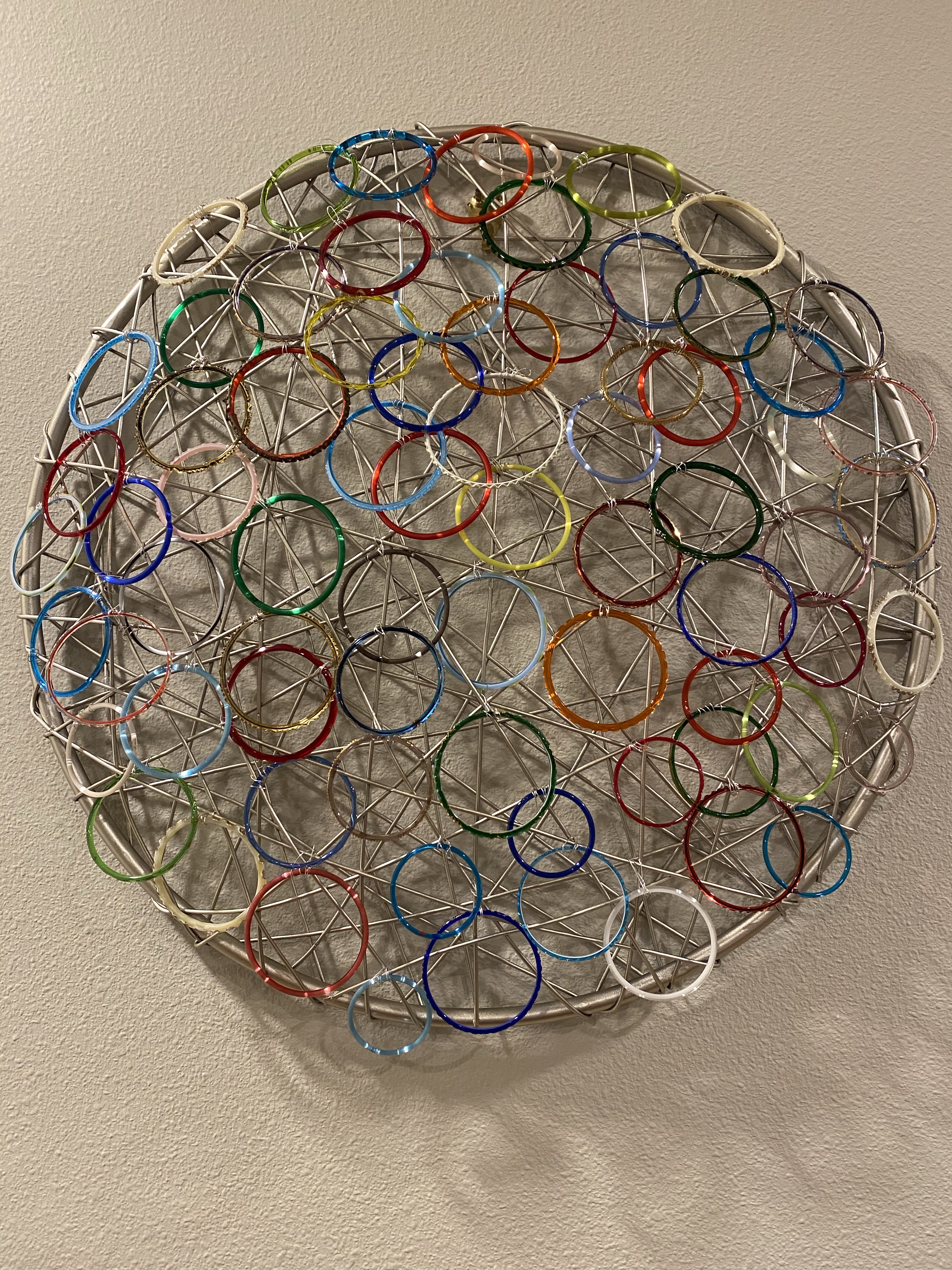

I came home from school with a sad look on my face. Something had troubled my seven-year-old heart and Mother wanted to salve my wound. She put aside her sewing and retrieved a box from the top shelf of her closet. Removing the lid, she held the box out for me to look inside. Something magical and precious lay shimmering in the soft cotton padding. Mother pulled out a rainbow of colored circles and spread them out on the bedspread.

“These are bangles from India. They’re made of glass and so they are fragile but you may hold them if you like.” I hesitated to touch them but Mother held one out and placed it in my open palm. It was dark red with delicate gold trim on the outer edge. Then she took the bangle, folded my fingers tightly into a wedge and slipped the red circle over my hand and on to my wrist. Color after color went on to my arm and erased my sadness.

“How did you get these, Mother? And when did you wear them?” My mother’s childhood in India was a source of great interest for me. I had heard my grandmother’s stories of their life in a village near Bombay where my grandparents were in charge of a mission school and medical dispensary but my mother rarely talked about her life there. Now I caught a glimpse of a ten-year-old girl named Lois attending school in the Himalayas, a thousand miles away from home. Each month her parents sent her a small allowance for personal expenses. Lois put most of it away and saved it for special trips to the local bazaar. There she would go with her friend Margo, straight to the glass bangle shop. There were so many colors and patterns and sizes to choose from! The bangles weren’t for dressing up or to be worn at all. Lois knew that they signified a married woman to the Indians. She simply liked them.

In 1926 Lois came to the U.S. to enter college in Indiana. The bangles came with her. She got married and the bangles moved with her from house to house, safe in their cotton padding in a box in the closet, until that day in 1952 when I came home crying. Occasionally she would bring them out again and we would “ooh” and “aah” at their beautiful fragility. For her birthday one year my father gave her a round crystal vase with deep lines etched into its surface. It served perfectly to hold the bangles. When sunlight struck the bangles inside the crystal ball hundreds of rainbows danced around the room.

With passing years Mother began to give away many beloved objects to her family. Perhaps remembering the day the bangles made me smile, she offered them to me to keep and treasure. I brought the bangles in their crystal bowl to my home in New Orleans and displayed them on a bookcase in my living room. When days of sadness and heartache came, I rested my eyes on the bangles. I imagined the women in India who were too poor to buy gold and silver, purchasing these bright glass circles to tell the world that they were married. The bangles began to represent the intertwining circles of love in my life, singularly beautiful and collectively a rainbow of strength and hope.

On a Saturday in late August 2005 my family and I heard dire reports about a hurricane named Katrina that was aiming for New Orleans. We hurriedly packed a few things and left town, five people and one old dog in our SUV, driving through the night to a motel in Houston. We expected to return home in two or three days and go about our lives. Early Monday morning we heard the first news reports about breaches in the levee system that protected the city and knew for certain that our house was one of thousands filled with water. All day we thought about how our lives had changed in the blink of an eye—or the crack of the levee.

Sleepless that night my mind traveled through my home, wondering what it looked like now. Without effort, the crystal bowl and its glittering glass bangles popped into my mind. Was it possible that such delicate objects had survived the storm? I knew the answer and my heart felt heavy. I could not form words to express my sadness. How would I ever tell my ninety-five year old mother?

Six weeks later we were settled in an apartment in Columbus, Ohio when word came that our neighborhood had reopened for residents to return to their homes in order to assess damage and salvage what they could. I traveled down the interstate past tall pine trees and utility poles stretched out along the highway like tinker toys. I drove into a city that had been my home for over thirty years but no longer looked familiar.

Emotions swirling, I didn’t know if I wanted to scream or cry when I arrived at my house and walked through the front door. A filthy brown line on the walls revealed where six feet of lake water had brewed for days. Mold and sludge and brown haze covered everything. The furniture had been pushed this way and that by the flood. I laughed at the chaos in the living room: the leather couch, now gray with mold, sat on top of the glass coffee table, every picture and mirror had fallen and shattered, every book opened up flat with words obliterated by mud. The teakettle had floated from the kitchen stove to the fireplace mantel and rested next to one of my husband’s shoes from the bedroom closet, suggesting decorations for a strange holiday.

And there before me on the hard concrete floor rested the crystal bowl, still filled with its rainbow of bangles shimmering in the sunlight. Like a soccer ball it floated, and as the water receded inch by inch, the bowl/ball gently lowered until it touched the floor. Not a single bangle had broken!

Beauty finds its way into ugly places, resting there silently until someone sees it. We need symmetry and color, harmony and single notes, things which startle and things that soothe. Words and sounds and patterns and ideas and textures and fragrances and flavors. I think of beauty as wholeness and completeness and possibility, as life itself. When we make a connection with something beautiful a little spark of healing energy passes through us. Take notice of beauty today.

Flood waters rising after Hurricane Katrina

Flood waters rising after Hurricane Katrina